This version of the essay is told as a conversation with my college classmate Mike Freed, in order to appeal to other classmates at our recent 50th reunion. A more technical version exists and is in search of a publisher. Both versions tell the same tale.

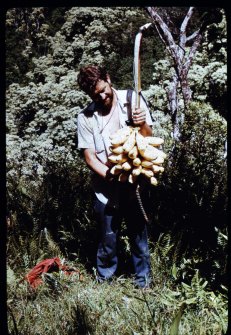

Mike Freed paddles toward exciting discoveries.

Old Men and Rivers

By: Wendell A. Duffield

January, 2012

Ask almost any knowledgeable Minnesotan where the mighty Mississippi River begins its 2,300-mile journey to the Gulf of Mexico and the answer will be, “At Lake Itasca, up in the northern part of our state.”

Itasca is one of the ten thousand lakes that decorate and submerge much of Minnesota. These lakes are bodies of water left behind as the melting snout of North America’s most recent glacier retreated towards its Arctic origins around 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. They’re recharged today by seasonal rainfall and snow melt. Though a member of such a very large family of lakes, Itasca has a small footprint (about 1.5 square miles) and shallow average depth (about 30 feet).

But Itasca’s fame is broad and deep. A modest breach in its north shore is where ten thousand and more visitors are said to have walked across the birth bed of the Mississippi River on a few properly human-positioned stepping stones, without getting their feet wet. A dry crossing is a sort of unofficial rite, an initiation to become a certified resident of Minnesota. Should someone slip and wet a foot or more, rules of the rite allow multiple attempts until success is attained. Only an inept or unable person would fail. And as Garrison Keillor repeatedly points out, so many Minnesotans are above average.

I’m one of the many initiates who succeeded at first try. I was six years old at the time I passed muster, with legs barely long enough to jump from stone to stone at the crossing. My mother recorded the event with a black-and-white snapshot, eventually lost in the chaos of the family-house attic. A lot of water has flowed down the Mississippi since then.

Now as a septuagenarian who was tossed by the rapids and spun in the eddies of formal education for two decades, followed by nearly a half century of navigating the experiences of a professional in the sea of geology, I find myself doubting that Itasca is the source of North America’s greatest river. This doubt has sprouted not from naiveté, but rather from earth-science factors that don’t fit into the popular Itasca scenario. And it continues to grow with time. I’ve concluded that all of us initiates to date may have been bamboozled by the Itasca tale, which is told as gospel to children before they are educated enough to be critical thinkers. As a concerned adult research scientist, I feel an obligation to publicly question traditional evidence of the river’s source before new generations of kids might be misled.

For the past few years, I’ve voiced my doubts to many listeners. And by speaking out, I’ve discovered how passionately adherents to the Itasca story do not want to hear an alternative view. Questioning of this oft-repeated “truth” seems to be equivalent to dissing one of Christianity’s Ten Commandments. Once chiseled into stone and sermonized over generations, such rules accrete a protective coating of question-proof armor for believers.

But I stubbornly persist. “Wait! My story holds as much water as that lake from which you believe the Mississippi River flows,” I explain to those who listen, but then react as if I’m attacking their sanity. “Just consider these facts, backed with scientific principles of …”

Before I can finish the sentence, derisive sounds drown out the information I want to explain.

Discouraging? Yes! But recently I unexpectedly encountered an independent human source of evidence that calling Lake Itasca the Mother of the Mississippi may indeed be a shaky, if not a false claim. And I’ve decided to write his story in hopes of reaching readers who are open to new ideas — people who might acknowledge that I’m not a wild-eyed heretic out to dash a Minnesota legend.

Allow me to introduce my college classmate, Michael Freed. Mike is an exceptional person whose curiosity seems unbounded. He’s a sponge looking to soak up information, simultaneously refusing to accept a new concept as valid without testing it himself. He also seems more interested in educating himself than helping to educate others. Selfish? I think not. He just wants to learn as much as possible before his mind begins to atrophy under the debilitating stress of time.

Having neither seen nor heard from Mike since graduating from Carleton College in1963, we two happened to reconnect at a recent class reunion, where he told me his take on the Itasca claim. So here’s his story. Read, open your mind, and see what you think. If you decide it’s malarkey that needs protesting, please contact Mike, not me!

A Conversation with Michael Freed

During an evening on-campus gathering of the class of ‘63 in one of the college’s new apartment units, Mike coaxed me to a quiet corner of our meeting room, relatively free of the noise from inane palaver of our classmates.

“Duff,” he began, as though I had expected to hear from him that night. “I’ve heard you say that Itasca isn’t the source of the Mississippi. I was at one of your geology talks open to the public.”

“Really?” I said in surprise. I’d been giving these lectures as a volunteer for continuing-education organizations. Most attendees were new faces for me.

Mike and I hadn’t been close friends during the college years. My aging memory seemed to remember him as majoring in one of the social (so-called) sciences — a path that allowed and invited multiple “answers” to questions, in sharp contrast to a more rigidly physical science such as my geology major.

“I didn’t see you. Why didn’t you let me know you were there?”

Before he could answer, I sensed the reason for his silence might be that Mike was still a loner. During our college years, while most students had their cliques of close buddies, Mike had been the introvert. In fun, we extroverts referred to him as Mr. Apostrophe, thinking we were quite clever to label him as I’m Freed — freedom being neither wanting nor needing to belong to a social group.

Mike’s answer tonight was “Cuz during the question period you were mobbed by doubters. I think I was the only one swayed by your tale. And what you said got me thinking about a way to test your ideas. That’s what I want to tell you about now.”

That focused my attention. I was ready to settle in and listen. A drink would help lubricate the conversation.

“Want a beer?”

“Sure.”

“Hamm’s?”

“No. Make mine Dos Equis.”

I retrieved two beers from the open bar provided by Carleton, whose motivation probably was to help loosen the purse strings of potential donors. Then Mike and I sunk into adjacent easy chairs.

“Cheers.” We clinked bottles and drank in toast. “So what’d you do to test my ideas about the Itasca source?”

His story began with “I took a canoe trip.”

“Canoe trip,” I echoed. “What for? To paddle up the so-called Mississippi from the Twin Cities to rediscover where Itasca is?”

“Nope,” came the reply from lips pursed in wry smile. “I put in a couple miles downstream from St Paul, paddled to the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, and pulled up on the bank — across from Fort Snelling.”

“And then,” I said, inviting him to offer some wise insight about that place.

“Well, then I sat and reviewed info I’d gathered about the spot. I figured that confluence held the key to understanding which of the two rivers deserved the name Mississippi upstream from there.”

It was my turn to smile, as I nodded in agreement, wanting to hear where the current of this conversation would flow.

“Bottom line,” Mike said, sounding as certain as an experienced CPA. “The present upstream names don’t agree with what the landscape tells me.”

Yes, I silently shouted as I made a fist of my right hand, thumb up, and held it out toward Mike. He was talking about physical evidence, not blind belief.

“I’d guess the names upstream from there are based on home-state politics or some similar blather, more than science.”

He punctuated that comment with two gulps of Dos Equis. I followed suit with Hamm’s.

“What Chamber of Commerce wouldn’t want to claim the source of the Mighty Mississippi as theirs?”

I interpreted that comment as a hint to where Mike’s canoe trip might end.

“Lookin’ upstream from where I sat,” he continued, “I think what’s named the Minnesota River should be the Mississippi. And what’s called the Mississippi I’d call Itasca or maybe somethin’ else.”

He leaned forward, pulled some notes from a hip pocket, and mumbled what sounded like something thousand cubic feet per second.

“I’ve got two reasons to change the names. First one is about the amount of water that each river carries to the confluence.”

This geologist could see that sociologist Mike had done key homework for his canoe-launched discovery trip.

“If flow was a lot more in one than the other, I think it’d make sense for the biggie to be called the Mississippi.”

He harrumphed, put on a professorial look and sound, then added, “The branch of a tree isn’t mistaken for the trunk.”

“Yeah. That seems logical to me.”

“I found information about water flow on the internet,” he said. “There’re seasonal and geographic differences in how much water comes in from upstream, depending on rain, spring snow melt and such. But averaged over a few years, the two rivers flow about the same. So there’s no convincing bigger-is-better argument for the way things are named.”

“Agreed.” I was hearing part of my own story from a pair of independent lips — lips of a person not trained in science, but aware of what a mute landscape can tell of its history.

“Let’s drink to that.” We clicked bottles, swallowed, burped and grinned.

“Next point,” Mike said. “My second reason for changing the upstream label from Minnesota to Mississippi is kinda complicated.”

“Go for it. I’ve got all the time you need.” Mike had already made this class reunion a winner. For once I was in no hurry to rush home from boring remember-when conversations.

He checked his notes again, while I fetched pretzels and peanuts from the bar.

“I’m no geologist, but I took that introductory course back in the day to satisfy a science requirement. I remember Profs Dunc Stewart and Eiler Henrickson telling us that mountain glaciers are like river systems. There’s the main tongue of ice plus smaller tributary branches that feed in from the sides.”

“Right. So?”

“The glacier ice flows more-or-less like the liquid water — just way way slower.”

“Right again. So?” I thought I knew where Mike was headed. I wanted to hear him reason it out, rather than coach him.

“The thick main tongue gouges out a deep valley. The thinner ice of side branches can’t keep up, so they gouge out shallower valleys.”

“Yeah. But you’re not telling me what that has to do with our river problem.”

“Hang on.”

Another swig of beer provided thinking time.

“When the glacial ice melts and becomes a system of rivers, you end up with a main river in the deep valley, and a bunch of smaller ones that feed waterfalls in from the sides.”

“You’re a good amateur geologist, Mike. We call those hanging valleys, cuz they’re perched way up there on the sides of the biggie. Think Yosemite Valley with its Bridalveil, Ribbon and other falls spilling in from the sides.”

We both squirmed, searching for comfortable butt support in old lumpy chairs.

“But I hope you’re not telling me that the river valleys we’re talking about here in Minnesota were carved by glaciers.”

“No. Water did the job. Stewart and Henrickson also taught us that water flowing south from the big North American glacier that was melting back a few thousand years ago created the valleys. And there was a whole lot more flowing down the Minnesota then than what’s considered to be the Mississippi above the Cities today.”

I decided to offer a little coaching in hopes of keeping his story flowing in the direction I preferred.

“Stewart also told you that for those glacier-melt days the Minnesota was called River Warren. And that today’s Mississippi, upstream of the Cities, was so puny that it hardly merited a name, most especially not Mississippi. It couldn’t keep eroding its bed down deeper and deeper as fast as Warren was doing for itself.”

“Exactly. So here’s my point,” Mike said. “There’s a waterfall called Saint Anthony’s where the Mississippi flows through Minneapolis. That’s my evidence for what you call a hanging valley — a small version of those hanging valleys in Yosemite.”

“Yes!” I shouted, drawing brief glances from classmates across the room. “I think the river history in the Twin Cities area is something like that. You’re a heck of a geologist for a sociologist.”

Mike smiled. We both squirmed again, seeking not-to-be-found comfort.

“Another beer?”

“Sure.”

I retrieved more vocal-cord lubricant. Now it was time to urge Mike upstream with his canoe-trip saga.

“So Mike. Once you decided the Minnesota River should be called the Mississippi, how far upstream did you paddle?”

“As far as I could.” He leaned forward and slowly shrugged his shoulders, arms outstretched — a furrowed-brow expression of pain painted on his face. “That paddling was damn hard work.”

“What’d you do for food and such?”

“There’re lots of towns along the way. I caught a few fish, too. Cooked stuff over driftwood fires and slept on sandy beaches.

“But here’s the main thing I noticed goin’ upstream. The valley for a lot of that stretch is huge — a few hundred feet deep and up to four or five miles wide. Makes the valley of the so-called Mississippi upstream from the Cities look like a mistake — like a shallow scratch across a smooth surface.”

“Thank River Warren,” I said. “Warren deserves most of the credit for the size of the valley of the Minnesota — and for the valley of the Mississippi downstream of the Cities too.

“Here’s an interesting tidbit for you. During its heyday, the amount of water flowin’ down Warren at its upstream origin was three times that comin’ out of the downstream mouth of the Mississippi today. Just remember, Warren was the outlet for gigantic Lake Agassiz, which kept gettin’ bigger as the snout of the melting glacier retreated northward.”

That was a sobering thought. Time for another swig of beer. Mike continued.

“If you want more description on what it’s like to paddle up the Minnesota, read Canoeing with the Cree by Eric Sev….”

“I’ve read that,” I interrupted.

“Then you know that lucky guy had help with the paddling.”

Another gulp of beer, maybe because Mike was remembering his solo sweat-generating trip. Then.

“About three-hundred miles and several days of sore shoulders later, I had to portage around a small dam where water is fed into the Minnesota, I mean our Mississippi, from the south end of Big Stone Lake.”

“More evidence of Warren’s work,” I said. “Big Stone fills a stretch where Warren eroded its bottom extra deep. The dam’s there to help control lake level for the convenience of folks living along its shores.”

“I understand,” Mike said. “So, now I’m paddling up a thirty-mile-long finger lake whose imaginary center line is the boundary between Minnesota and South Dakota. I stayed right to keep my trip and our Mississippi in Minnesota.

“I loved that part. No current to fight. Good fishin’ too.”

He stretched, flexed his arms and shoulders, and smiled. We crunched a few pretzels and washed them down with a beer chaser.

“I know that lake,” I said. “I fished and swam there as a kid.”

Mike continued. “Then you know that at the north end of Big Stone, the state boundary veers overland, a bit to the left. I stayed right and entered what’s labeled Little Minnesota River on maps.”

He hesitated before a mild venting.

“Can you explain this to me? Little Minnesota! What sense does that name make? Nobody’s ever called the river stretch between Itasca and Lake Bemidji the Little Mississippi! So why’s this the Little Minnesota?!”

“Who knows! It’s another bit of nonsense about how rivers are named. The system seems controlled by whims instead of logical uniform guidelines.”

“Alright. So you and I agree that when I left Big Stone Lake I was still paddling up our Mississippi. Then, bingo, I’m suddenly in Browns Valley.”

“Yup. My hometown.”

“I know.” Mike shifted his body around, and formed a gotcha expression that I took as shifting his thoughts, as well.

“Now comes where I part ways with Sevareid and his paddling partner Walt Port. Those two portaged for a mile across a continental divide that runs east-west through Browns Valley, then put into Lake Traverse and headed north, goin’ downstream from there all the way to Hudson Bay.

“But my route from BV took a twist that the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce won’t like if I’m still on the Mississippi,” he continued. “The path of the so-called Little Minnesota swings westward, enters South Dakota, cuts across that side of Warren’s valley wall, and heads off into a Sioux Indian Reservation.”

Mike and I now had our upstream Mississippi in South Dakota, and heading northwest. I kept quiet, to see how Mike would describe what had been some of my home turf while growing up.

“Here’s more naming nonsense,” he said. “I’m now paddling up a river named for Minnesota, but all except its last mile or so is in South Dakota.”

We raised right hands, did a high-five slap of agreement, chewed peanuts and did the beer wash down.

“Another ten miles, and the goin’ got tough. I’d timed my trip for the high water of spring, but banks of the river were closin’ in toward the width of my canoe anyway. I had to pull out and call for help.”

Mike leaned back relaxed, as though his tale was complete, but added “Info from the internet says the river I pulled out of starts near a tiny town called Veblen, another twenty miles upstream. I drove up there to take a look.

“There’s no lake. Just open country where rainfall and saturated ground feed streamlets that join to become our baby Mississippi.”

We settled back into our chairs and audibly exhaled in joint conclusion. We polished off our beers.

“Well, that’s my story,” Mike said. “And now it’s yours if you want it. You seem to like to talk and write. I prefer to keep movin’ and doin’.”

He squirmed. “Speaking of movin’. My bladder needs to.”

Mike stood, made his way across the room and through the door labeled GUYS. Consumption of two beers in one hour creates that kind of need, especially so for us old guys.

I waited. Mike didn’t return. I went to drain my processed beer. Mike was not to be found. Similar to graduation day of ’63, he once again silently disappeared. Mister Apostrophe was alive and mobile.

Later

I heard from Mike, via email, about a year later. Meanwhile, I had dusted off my 1963 ALGOL and discovered that he graduated as a biology major. He had more science in his background than I had thought during our earlier beer-soaked Mississippi conversation.

His email described a recent solo hike along the Great Rocky Mountain Continental Divide from Mexico to Canada. He asked if I wanted to meet and discuss why so many people don’t really understand what a continental divide is. Later, we did meet; that’s a story for another time.

After the river conversation with Mike, I’ve continued talking about the Mississippi and how rivers are named, where people will listen. I suspect I’ve convinced no one of the need to even consider changing some labels in this gigantic North American drainage basin. Even so, I may have enlightened a few listeners about how arbitrary the official naming of rivers can seem. Some readers may remember when part of today’s Colorado River, the part actually in that state, was called the Grand. Pick any two river systems with a main trunk and tributaries, and see if you can define a consistent and logical set of rules for the names.

If nothing else of value has transpired, I think I finally enlightened myself as to why I’m interested in the mundane and somewhat trivial topic of naming rivers. The words old and forgotten are involved.

Old River Warren did nearly all the heavy lifting, that is to say the erosion that plucked and carried rock and silt to the Gulf of Mexico, thereby sculpting the valleys now occupied by the Minnesota River and much of the Mississippi below their confluence.

I can easily imagine generations of awe-struck people back in Warren’s time, watching this almost unimaginably massive river coursing over their lands. There would have been no wading across. One Native American, whose remains are known today as The Browns Valley Man, was ceremoniously buried in a gravel bar of River Warren about twelve thousand years ago, a location perhaps selected out of respect for such a powerful presence of nature. I wonder what that man and his forerunners called the river. And if they could talk to us today, I wonder what they would say about the names Warren and Minnesota and Mississippi.

So far as I know, Warren is the first name to be recorded in printed literature for this drainage track. But Old Warren doesn’t get broad credit and appropriate recognition for all of its work. Bummer! Doesn’t seem fair!! I suspect that other than some geologists, few people know the story of River Warren. The truth is that today’s Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers are nothing more than opportunistic carpetbaggers by comparison!

As a kid growing up in its broad deep valley, I didn’t know about River Warren either. Yet I skied and sledded on Warren’s valley slopes. I hiked and camped within the wooded side rills. I swam and fished in the Big Stone and Lake Traverse dregs of Warren’s huge powerful water. I skated on and fished through their winter covers of ice. At age fifteen, a wet-behind-the-ears certified pilot, I landed my dad’s Cessna 120, solo, on the looking-glass smooth and slippery frozen surface of Traverse. That adventure, too, is a story for another time.

Now that I know your story, I thank you River Warren. You created a magical playground for past and future generations of kids like me to enjoy. You and this old geologist are soul mates in ways that many might not imagine, whatever the official names are for the waters in your valley today.

Recent Comments